So far, we've looked at how we can find the top words from a text as well as the average word length in a text. There are many more interesting things we could do to analyze textual or other data. One common term for such analysis is "data science". If you're interested in learning more about how to use Python to analyze real data, consider taking the Data Science Foundations course DATA C8.

If you're trying to decide between DATA C8 and CS61A: DATA C8 and CS61A don't overlap very much, and there's no reason you can't take both. We expect that there are many students who will take CS61A followed by DATA C8, and many students will take DATA C8 followed by CS61A. If you're pretty sure that you're interested in being a CS major, you'll need to take CS61A.

Both assume no prior programming experience (not even CS10). CS61A focuses much more on traditional computer science topics. It'll feel like an advanced version of CS10 that moves quickly and covers a broad variety of topics, largely oriented around abstraction and programming paradigms. By contrast, DATA C8 is more of a class in applied techniqes for analyzing real world data. The syllabi can be found here: CS61A and here: DATA C8.

While this exercise is optional, it's definitely within reach of everyone in CS10. We encourage you to try this activity, though if you don't have the time that's fine. This exercise is great practice with Python data structures, so you might consider doing it while you're studying for finals, even if you don't do it the same week as the rest of this lab. It also provides a rough sense of what a small 61A project will look like: There will often be a specification that takes some time to fully understand, followed by a series of incremental challenges.

Most of the TAs will not be familiar with this new exercise. If you ask for help, be friendly to them since they'll be figuring it out along with you.

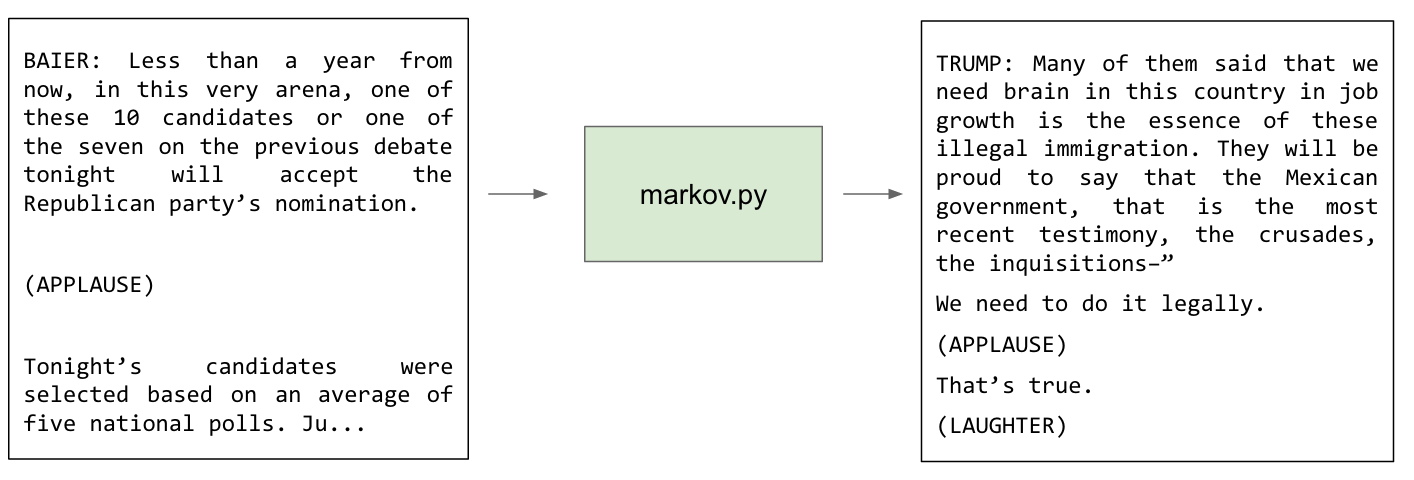

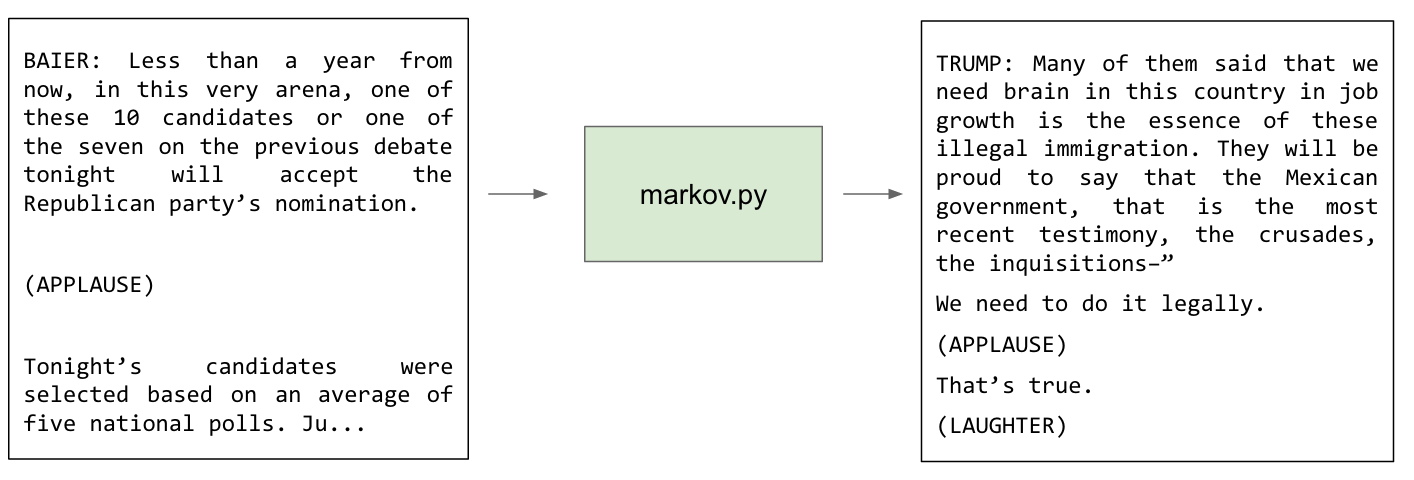

So far, we've talked about what is called "natural language processing". We feed our algorithms some text data, and it spits back out something else. The reminder of this lab is an exercise in "natural language generation", where we'll train a model how to speak and have it generate new text for us. We'll use the simplest possible model, but the results may still surprise you in their sophistication.

Let's start with some terminology. Given a text, the set of k-grams in that text is the set of all texts of length k that appear in that text. For example, if our text is "the ether" and k = 3, then the 3-grams that appear are "the", "he ", "e e", " et", "eth", "her", "ert", and "rth". The mysterious last two 3grams are "ert" and "rth" because we pretend that the text wraps around. You could also build a markov model that does not involve wrapping the text like this, but it'll be handy for our ultimate goals (explained later).

The model that we'll be building of our text is a Markov Chain. A Markov Chain is a table of information about how frequently particular characters follow each unique kgram appearing in the text. As an example, the Markov Chain for our text with k=3 is:

frequency of probability that

next char next char is

kgram freq e h r t e h r t

-----------------------------------------------------------

the 2 1 0 0 1 0 1/2 0 0 1/2 0

he 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0

e e 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1

et 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0

eth 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0

her 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1

ert 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0

rth 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0

Each kgram in the sentence appears exactly once, except for "the", which appears twice: Once at the beginning, and once in the middle of the word ether. Among the two times that "the" appears, one time it is followed by a space, and the other time it is followed by an r.

Recall that we treat our text as circular, i.e. we pretend that the string wraps around back to the beginning after the end. This results in the 3grams "ert" and "rth". These kgrams start at the 2nd to last and last character of the string respectively.